On June 5, 2019 the Federal Crop Insurance Corporation (FCIC), which oversees the entire federal crop insurance program, announced important changes to the Whole Farm Revenue Protection (WFRP) policy as a result of legislation passed in the 2018 Farm Bill. We at the National Center for Appropriate Technology (NCAT) have been working since 2008 to support and improve the whole farm revenue approach to insuring farms and ranches. The National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition and many others have also helped and after these many years of effort there is now a nationwide policy to insure the revenue from the whole farm and not just a single product.

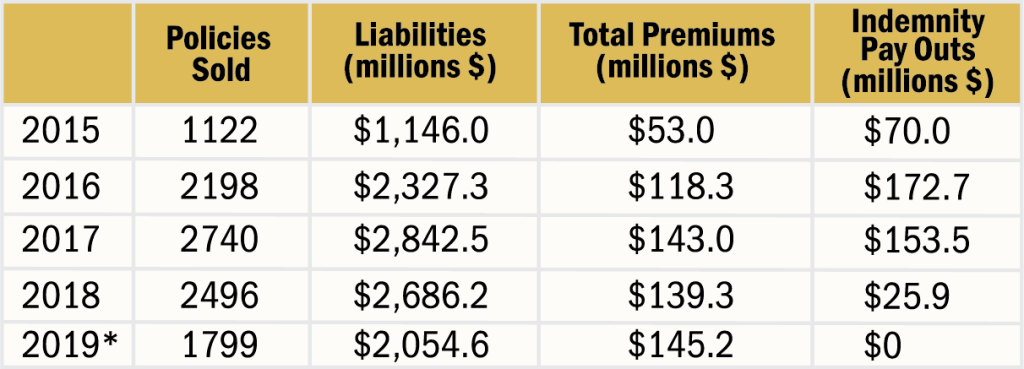

Since its creation as part of the 2014 Farm Bill, there has been a general upward trend in the use of WFRP with the exception of 2018 as can be seen in Table 1.

In addition to providing whole farm revenue protection, WFRP offers a means to provide some level of subsidized crop insurance protection for farms of all sizes and any type of crop or livestock product. Also, because coverage is based on the farm’s historic adjusted gross revenue, the organic value of the farm’s production is protected. Though limited to farms with less than $10 million dollars in gross revenue, the WFRP program now provides the greatest extension of federal crop insurance coverage to all types of organic farmers in the history of the federal crop insurance program. Finally and perhaps most importantly, WFRP is the first agriculture insurance policy that provides substantial premium discounts for those who grow more than three crop or livestock products. It is a product ideal for organic and sustainable farming operations.

Understanding and demonstrating the recent change in WFRP can be seen in the following example drawn from real world data of an organic field crop farm in Montana, my home state.

The organic farmers who provided this example data are Doug and Anna Jones Crabtree of Vilicus Farms, 50 miles north of Havre, Montana very near the Canadian border.

Doug and Anna in any given year will grow over eight different types of grains, oilseeds and legumes on 7,400 acres. Many of their crops are very specialized like for instance, emmer wheat.

Essentially, the recent change in WFRP explained below will significantly improve coverage for those using this policy.

Smoothing Historic Revenue

The critical change made has been to “smooth” the impact of historic high-levels of revenue variability that many farmers experience who use WFRP. These changes are modelled after the same “adjustments” that are made to a farmer’s “actual production history” (APH) in single crop revenue policies that most major organic and non-organic commodity farmers use. The difference is that the adjustments are made to historic revenue rather than the historic yields of a single crop being insured.

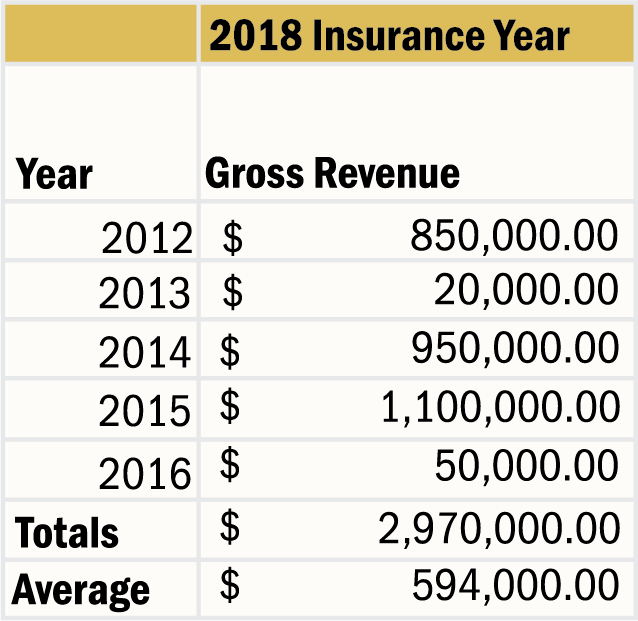

This example is based on Vilicus Farms data and applied to a hypothetical 3,000 acre organic field farm in Hill County, Montana. This is the same county where Doug and Anna farm. The year of insurance is 2018. Though hypothetical, the estimates are roughly based on a realistic expectation of what an organic grain farmer’s revenue history could be. Table 2 is the organic grain farmers’ five years’ adjusted gross revenue history experience.

The expected gross revenue for the insurance year, 2018, is $1 million dollars, which in this example, has been previously approved by the farmer’s crop insurance agent. In this example, 2017 is a “skip year”, which is typical due to the grower not yet having the final figures of gross revenue from tax returns. Under current policy rules, the premium would be based on the $594,000 average, and at an 85 percent coverage level, the farmer could cover up to $504,900 of revenue in the insurance year. What this means is that the farmer would not receive any insurance indemnity until revenue drops below $504,900. This is called the “trigger” point.

Given the historic variability of the revenue of this farm, the “average” does not come very close to covering the realistic expectation of the farmer to obtain $1 million dollars in gross revenue in 2018. One could say the farmer is “under-insured” in this case or at least it is a high-deductible policy. Doug and Anna assured me that this kind of volatility in gross revenue is a realistic situation for many farms in Montana and may become even worse with further climate disruptions.

There are three expected changes* to how the average historic adjusted gross income will be determined. These “history smoothing options” are:

-

- Each year that the historic revenue is below 60 percent of the producers’ average historic revenue will be replaced with the average revenue, calculated from the same set of years, with gross revenue figures for 2013 and 2016 replaced with $356,400 (60 percent of $594,000). Using these figures the average gross revenue will be $722,560

- The lowest historic revenue year will be dropped and the average will be based on the remaining four years of adjusted gross income. This calculation would result in an average gross revenue of $737,500. It’s not clear at this time which average calculations (#1 or #2) will take precedence.

- The approved, insurable revenue for the insurance year (in this case, 2018) will be at least 90 percent of the previous years. This prevents producer’s insurance guarantee from dropping dramatically year-to-year.

*These changes to the WFRP policy have been approved by the Federal Crop Insurance Corporation (FCIC) in June of 2019. The FCIC is the governing body for all crop insurance in the US. Details of implementation of these policy changes have not been officially released by USDA’s Risk Management Agency as of publication date of this article.

So the adjustments to this example would be:

-

- 60 percent of 594,000 is $356,400 and therefore this replaces the values in 2013 and 2016. The new, recalculated average with $356,400 replacing the 2013 and 2016 figures is $722,560. So, at an 85 percent coverage level, the trigger point, or the revenue level at which insurance indemnity kicks in is when revenue drops below $722,560 X .85=$614,176 instead of $504,900, as currently calculated. The bottom line is that more revenue is insured.

- The approved revenue for the insurance year is $1 million dollars, 90 percent of that is $900,000. “Approved revenue” is the level of revenue that has been approved for revenue insurance by the farmer’s crop insurance agent. Keep in mind that the highest level of revenue insurance offered under WFRP is 85 percent, so the insurable revenue in this case is $900,000, but the trigger point would be 85 percent of that figure: $900,000 X .85= $765,000.

Bottom Line

These changes will make WFRP a better product over the longer-term given the often high degree of variability of a farmer’s income, whether organic or not. The total premium cost for this new adjusted WFRP policy would have been $103,923 dollars. With the federal subsidy the farmer pays $ 37,571 dollars, not an insignificant cost. However, it is important to note that many of the highly specialized organic crops grown and used in this example, such as emmer wheat and kamut, are very valuable and uninsurable in any other way. Also, it is critical to recognize that this unique policy provides some protection against revenue reductions, and not just losses attributed only to yield loss. Revenue is price X yield and both are at risk. Often there are yield risk policies for unusual specialty organic crops in some geographic locations, but rarely are these revenue policies. For example, I try to grow fresh market tomatoes in beautiful Butte, Montana but except for a WFRP policy, I would be unable to insure from price and yield risks.

Coming Attractions: Provisions Specific to Hemp

WFRP will allow coverage for industrial hemp production for the 2020 crop year with the following restrictions:

-

- Hemp must be produced in compliance with applicable plan (State, Tribal, or Federal).

- Hemp must be grown under a marketing contract.

- No replant payments will be offered at this time.

- “Hot” hemp will not be considered an insurable loss at this time. Hot hemp occurs when THC concentrations spike above 0.3 percent due to crop stress and cross-pollination.

Jeff Schahczenski, is an Agricultural and Natural Resource Economist, with the National Center for Appropriate Technology (NCAT). NCAT also implements ATTRA, the National Sustainable Agriculture Information Service through a cooperative agreement with the United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Rural Business-Cooperative Service. ATTRA’s website, www.attra.ncat.org, has information about sustainable and organic production of crops and livestock, as well as an updated version of Biochar and Sustainable Agriculture. ATTRA runs two toll-free lines which growers can call to ask any question related to organic or sustainable agriculture (800-346-9140, and Spanish toll-free, 800-411-3222).

Resources:

ATTRA. www.attra.ncat.org, toll free lines 800-346-9140 (Spanish: 800-411-3222)

Particularly helpful publications, videos, podcasts are available at ATTRA Crop Insurance

Documentation and Record Keeping for Whole Farm Revenue Protection (WFRP)

National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition (NSAC)

http://sustainableagriculture.net/

Vilicus Farms. https://www.vilicusfarms.com/

USDA Risk Management Agency (RMA)

www.rma.usda.gov/

This site is an excellent resource for all RMA programs, specific policies, and general risk-management tools. The following are some important links within the website:

-

- Basic description of policy types

www.rma.usda.gov/policies/ - State profiles of policies offered and their use

www.rma.usda.gov/pubs/state-profiles.html - Maps detailing policies that are offered in particular counties https://prodwebnlb.rma.usda.gov/apps/MapViewer/index.html

- Premium Cost Estimator for all polices

https://ewebapp.rma.usda.gov/apps/costestimator/ - Crop insurance agent locator https://www3.rma.usda.gov/tools/agents/companies/

- Whole-Farm Revenue Protection Policy https://www.rma.usda.gov/policies/wfrp.html

- Requesting insurance not available in your county

www.rma.usda.gov/pubs/rme/requestinginsurance.pdf

- Basic description of policy types