Organic farmer John Teixeira from Lone Willow Ranch near Firebaugh, California, first started working with conservationists from United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) when he was already an experienced farmer with more than a decade of experience under his belt and a head full of ideas he wanted to try.

The experienced—and ever experimental—Teixeira is on his seventh contract with NRCS—and is always looking for new, push-the-envelope ideas for farming ecologically. He also appreciates that NRCS can help him plan and pay for the new conservation approaches. One of the five activities Teixeira is currently pursuing with NRCS is to completely (or nearly completely) source all his needed nitrogen on-farm—primarily by using manure and legumes in cover crop mixes.

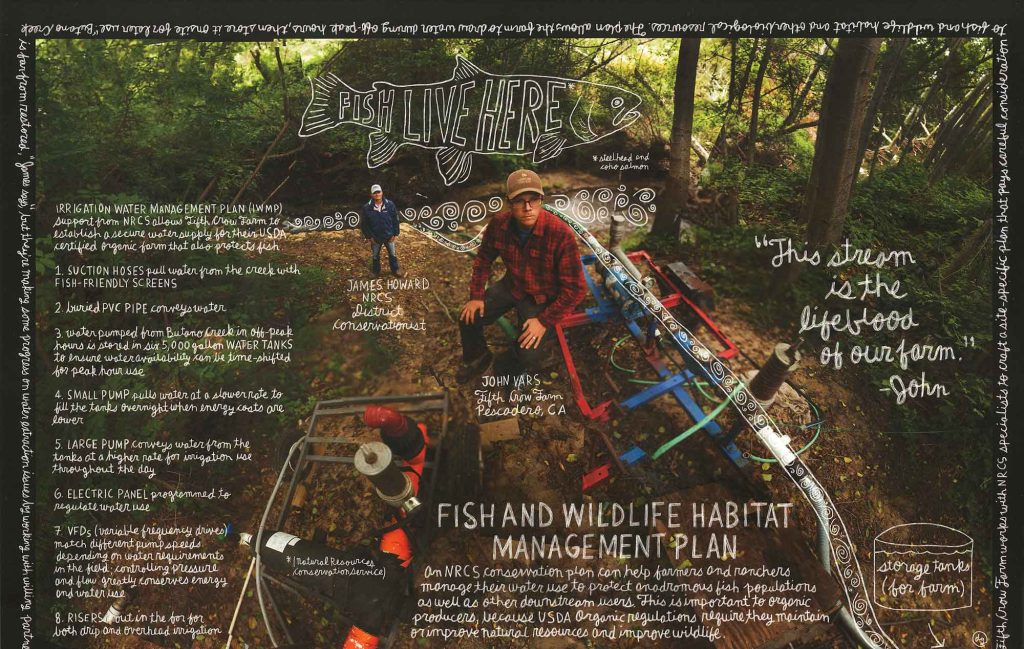

One hundred and fifty miles away on the Pacific coast near Half Moon Bay, Calif., organic farmer John Vars of Fifth Crow Farm visited with his local NRCS conservationist, Jim Howard, even before he planted his first crop.

Vars sought out NRCS expertise for upfront, planning basics like pipeline placement, drainage and soils information, and where best to place a hedgerow before he began applying for financial assistance.

There is no wrong time to visit NRCS for the first time.

The path to the office door may be highly personal for each farmer, but NRCS conservationists are happy to meet farmers where they are—beginning or experienced—organic, conventional or transitioning. All are welcome to access the technical services that NRCS has provided for over 80 years and the financial services available through Farm Bill programs.

Here is a brief primer on the available options:

Top Organic Practices Used by NRCS Customers: Self explanatory

Conservation Planning

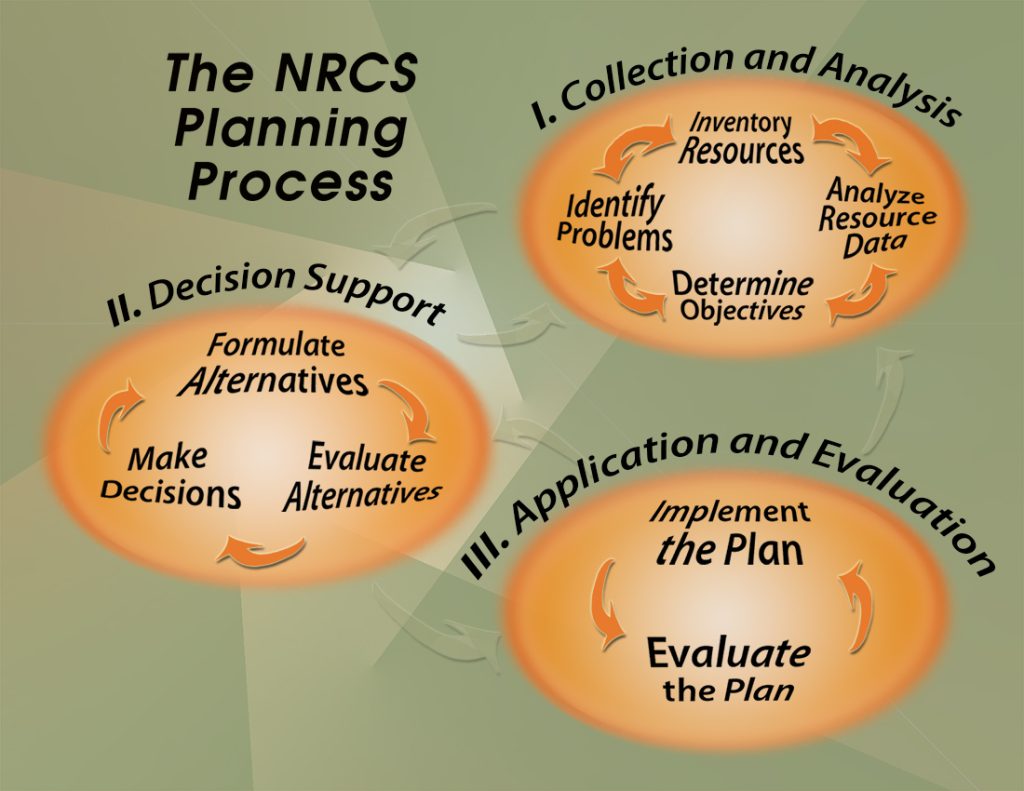

Few of us would build a house without a blueprint. Building a successful conservation approach to farming merits the same comprehensive forethought. NRCS has a well-respected 9-step planning process that has been used successfully by tens of thousands of farmers in the last 80 years. It begins with a resource inventory and is then based on the goals of the farmer. Options are provided and the farmer is the sole decision maker. The final step is evaluating the results, tweaking where needed and repeating the process.

Vars offers this comment regarding the value of this planning process:

“When you first start farming, you have ideas of what you want to do to be sustainable and successful, but you can’t afford it. When you can afford it, you may find it hard to go backwards—like where you want a road you may have already placed your hedgerow.”

Teixeira, too, has done significant conservation planning since beginning work with NRCS in 2009—first working with conservation planner Rob Roy, and later, with Sheryl Feit. Feit says, “Through the years John’s goals have changed. The NRCS planning process gives us the flexibility to continue to adapt our approach and work with him on his evolving goals.”

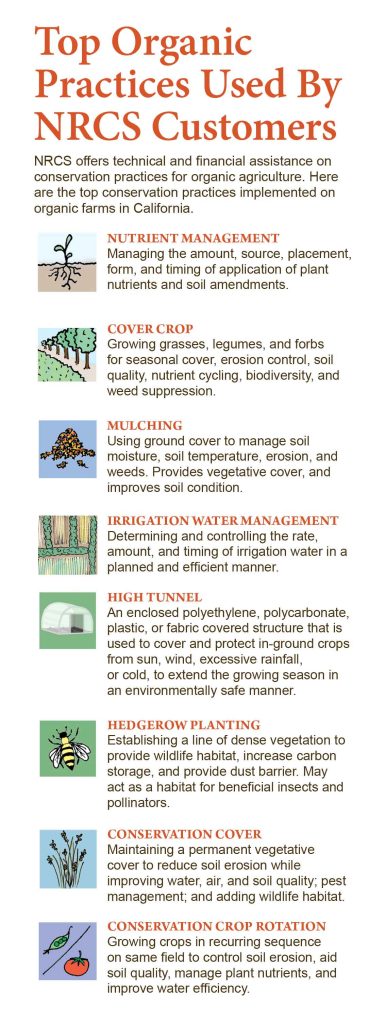

Once goals are established, conservation practices are selected to answer the farmer’s particular needs and priorities. The NRCS has a time-tested catalogue of well over 100 conservation practices to call into play, though a given land use (row crops, orchards, grazing, dairy, forestry etc.) in a given geographic location will usually lend itself to a particular subset of these conservation options.

In California some of the most popular conservation practices used by organic farmers in recent years have included the following: nutrient management, cover crops, mulching, irrigation water management, hedgerow plantings, conservation cover, crop rotation and high tunnels.

The conservation practices seek to address resource concerns targeted to improve the farm’s soil, water, air, plants, animal and energy needs.

Both Teixeira and Vars have used well over a dozen separate practices including many of those listed above.

Don’t Forget the Critters

Beyond the significant needs of running a farm, organic regulations also require that producers maintain or improve natural resources and wildlife. Both Teixeira and Vars have worked with

NRCS to do so.

Recognizing the unique habitat opportunities on his ranch—which lies between the San Joaquin River and the Lone Willow Slough—Teixeira has planned and used NRCS practices to make room for fish and wildlife on his ranch. Does that create a problem? “Well, they may occasionally get a chicken that has strayed too far, but that’s not really a problem,” Teixeira says philosophically.

for fish and wildlife on his ranch. Does that create a problem? “Well, they may occasionally get a chicken that has strayed too far, but that’s not really a problem,” Teixeira says philosophically.

Fifth Crow Farm has the unique challenge of drawing water from Butano Creek which is also used by steelhead salmon. To provide for the farm’s irrigation needs while minimizing impact on the fish, Vars and NRCS have collaborated on engineering a system of pipes, pumps, variable frequency drives, risers and a storage tank. “This stream is the lifeblood of our farm,” says Vars. The unique irrigation system helps balance the needs of the fish and of the farmer that both rely on that stream.

Professional Expertise

NRCS employs a diverse cadre of natural resource professionals who provide the expertise needed to work with farmers and ranchers to plan and apply conservation practices. These conservationists include agronomists, rangeland specialists, soil scientists, foresters, engineers, biologists and more. Not all of these will be found in a given field office (there are 54 field offices in California—typically one per county) but experts can be drawn upon as needed to explore a given conservation dilemma in more depth.

Additionally, NRCS partners with many resource specialists who can complement and deepen the expertise on staff. Resource Conservation Districts, university extension specialists and dozens of others collaborate to create a sort of “localized conservation internet,” looping in related specialists in entomology, ornithology, air quality, conservation easements, environmental regulations, energy and more.

Financial Assistance

In the real world, the difference between having lofty ecological goals and applying them across the landscape often comes down to money. Farm Bill programs provide a number of tools to help make goals reality.

Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) and the National Organic Initiative (NOI)

EQIP is a popular program that shares with the farmer the cost of applying selected conservation practices to the landscape to realize the farmer’s conservation goals. In recent years California NRCS has invested almost $100 million annually using this program. Typically, EQIP provides roughly half of the cost of most practices and is paid as a reimbursement once the practice has been implemented and verified. EQIP is a competitive program (one out of every two to three applications is funded on the average) and projects are ranked for environmental benefits. Producers interested in organic systems should realize significant environmental benefits and thus are often well positioned to be funded.

In addition to the “general” EQIP pool, organic and transitioning farmers have an additional option available only to them: the organic subportion of EQIP called the National Organic Initiative (NOI). Most of the practices mentioned in this article can be funded through either general or organic EQIP. However, since the organic funds are available only to organic and transitioning producers, the competition is often less when competing in this pool.

In the new 2018 Farm Bill, which rolls out in fiscal year 2020, the amount that farmers can get through NOI has increased to $140,000 over the life of the five-year Farm Bill. Furthermore, the annual cap has been removed so for large projects, that entire amount could be used in one year.

Farmers and ranchers can get up to a maximum of $450,000, through the life of the 2018 Farm Bill using a combination of NOI and/or general EQIP financial assistance.

To summarize, there is more money available in the larger pool of general EQIP funds, but there will also be more competition. Organic farmers are welcome to apply for either. Nationally, more than 1500 organic farmers have received EQIP contracts in the past three years, representing an Agency investment of more than $42.6 million.

Transitioning to Organic

An Organic System Plan (OSP) is completed by those who wish to be certified organic. NRCS Technical Service Providers (TSPs) can help producers develop a Conservation Activity Plan for Organic Transition (CAP 138). CAP 138 consists of three sections: Resource Inventory, Erosion Control Inventory, and Summary Record of Planned NRCS Conservation Practices. The Resource Inventory section may serve as a portion of the farmer’s OSP.

Farmers and ranchers should begin by working with NRCS to develop a conservation plan for their operation. Then, a TSP can develop a CAP 138 for transition and producers can apply for financial assistance to implement conservation practices or enhancements. Nearly 1000 transitioning farmers across the Nation have received CAP 138 contracts in the last three years totaling more than $15.4 million.

Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP)

John Teixeira–by himself and in combination with his brothers—has had four EQIP contracts—both general and organic. At this point John has a comprehensive conservation approach applied on most of his operation. John is now on his second Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) contract.

Farmers like John who already have applied significant conservation work on their operations may be ready for CSP—which plans and pays farmers to maintain and further enhance conservation practices on their operation.

Using John as an example, he has established a comprehensive conservation system on his ranch but wants to continue to find additional ways to reach a higher level of stewardship. Using CSP he is undertaking new approaches—such as intercropping, sourcing 90 percent of his nitrogen on-farm, and using a deep-rooted cover crop to improve infiltration.

John says that the ideas and insights he gains through his CSP enhancements have also given him good ideas for trying on his conventional acreage that he farms with his brothers. Currently, he says, he is working on ways to bring his intercropping approach to conventional row crops.

Applying for Financial Assistance

When applying for EQIP, especially when applying for the first time, producers should be mindful that they will need to fill out forms providing USDA with information that confirms that they are eligible to participate in these public-funded programs. USDA employees can help with the legal and financial forms that will make it possible to receive funding. Most of these forms are not required for farmers requesting only conservation planning and technical assistance.

Special Situations

Most EQIP contracts pay producers approximately half of the cost of structures or management. Benefits for organic producers may be higher due to the typically greater costs involved in farming organically. Additionally, payment rates are typically higher for those who have farmed less than 10 years (considered beginning farmers and ranchers) and for those with limited financial resources (defined on a county by county basis). Beginning farmers and ranchers who served in the U.S. Armed Services will receive an application preference in certain EQIP and CSP funding pools. Please inquire with your local NRCS service center for more information if you are a military veteran.

Plant Materials Center

NRCS is assisted by special facilities called Plant Materials Centers (PMC) that are dedicated to finding innovative ways to use plant materials to address resource concerns such as erosion, pollinator habitat or better soil health. In California the PMC in Lockeford has a robust program that provides demonstration gardens that are often the site of workshops and discussion groups. The PMC is a respected resource and site for continuing to find better conservation approaches. John Teixeira is currently trying to find a better cover crop approach for the hot, arid summer conditions in California’s Central Valley. As is turns out, that is a key focus for the PMC as well.

Other USDA Assistance for Organic Growers

In addition to the many conservation services organic farmers can find at NRCS, there are other USDA agencies and programs that can also offer important assistance. Two examples are farm loans and microloans through the Farm Services Agency and the cost share assistance that helps pay for organic certification. In California the help with the certification fees are administered by California’s Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA).

Getting Started

While the internet and other farmers are always a rich source of information, the best way to delve into the conservation opportunities discussed in this article is to get to know the conservationists at your local office. NRCS has 54 offices in California—typically an office in each county.

Working with farmers is what NRCS conservationists love most—and the relationship is mutually enriching. “We always love it when John comes into the office,” says Feit, “he always challenges us with his new ways of thinking through a situation.” Jim Howard who works with John Vars in Half Moon Bay, couldn’t agree more. “Farmers in my area are idea machines and we just love engaging with them to find solutions for the land,” he says.

The NRCS field office director is called a District Conservationist and they are assisted by soil conservationists and/or a range of specialists. It’s always a good idea to call ahead to make sure they have put aside time to discuss your farm and your concerns. You can find your local office at https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/main/ca/contact/local/.