This article describes theproduction system and handling practices currently required to market poultry products–eggs and meat–as certified USDA organic. It also discusses the substantive overlap and continuum in goals and practices among “organic” and “pastured” and “humane” poultry production. It addresses the main commonalities and a few key distinctions between systems and practices in the growing field of poultry production. Finally, it highlights the need for transparency and integrity with respect to product representation, both within and beyond the organic label.

Introduction

What image does the phrase “organic poultry production” conjure up in the mind of the American consumer? Many people are likely to imagine idealized happy hens on verdant pastures (like the pictures in this article). Perceptions of organic production system practices may overlap, and descriptions blur with less rigorous marketing terms, such as “cage-free,” “free-range,” and more rigorous “humane,” and “raised on pasture,” to name just a few. Many branding terms (paired with clever packaging and graphics) vie for customer attention in the marketing of poultry products. The complexity of terms and standards can confuse or even mislead the uniformed consumer.

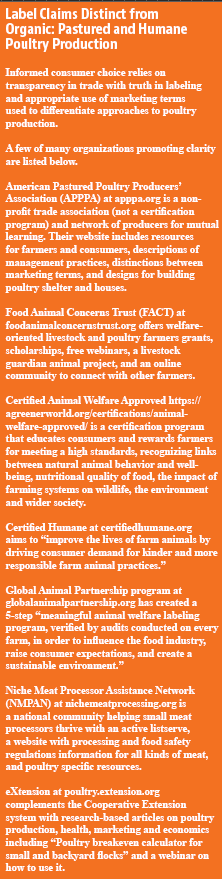

This article reviews the main sections of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) organic regulations for poultry production and discusses the different marketing terms used. Laws lead to creation of regulations that set standards for trade. Government standards, such as grading, food safety, and labeling are requirements that every producer must meet in order to sell their products. Beyond government requirements, many voluntary programs provide opportunities for producers to differentiate products in the marketplace, using terms with legal definitions, unregulated descriptors, or third-party certification programs. Some of these have minimum standards to qualify for certification; others provide levels or steps, and expectations for continual improvement (for details see sidebar on Page 6).

Producers can choose to pursue such voluntary certification options in response to the priorities of buyers, whether they are distributors or direct-market consumers. Assurance of clear standards and consistent enforcement of those standards boost consumer confidence and facilitate trade. Producer priorities and consumer values may include poultry health, production efficiency, whole farm productivity, environmental stewardship, animal welfare, food quality, product accessibility, and cost.

USDA Organic Regulations

USDA Organic Regulations

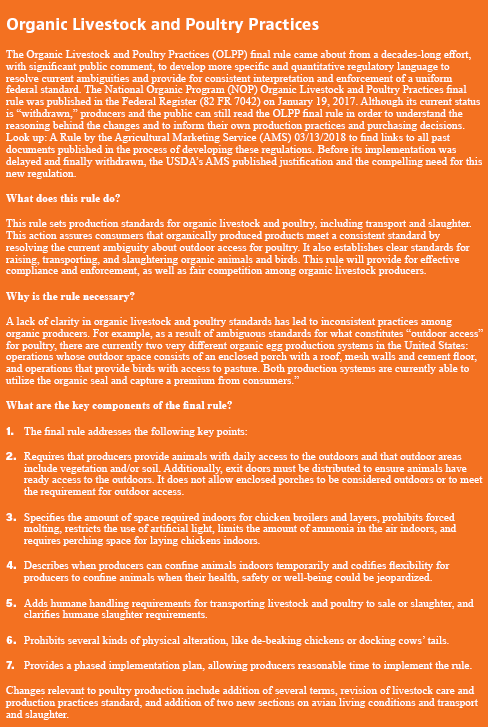

While this article focuses on current USDA regulations which are qualitative and goal-oriented, it is appropriate and important to acknowledge that, in the words of USDA, “the variability in outdoor access practices among organic producers threatens consumer confidence in the organic label.” National Organic Program (NOP); Organic Livestock and Poultry Practices. More quantitative and prescriptive regulatory language in USDA organic regulations would help level the playing field with respect to outdoor access and would give consumers more confidence in the organic label. There is a significant contrast in practices between two main types of poultry operations that, at this point in time, may both be certified organic: those that use barn- or aviary-based production with enclosed porches and no direct contact with soil, and those whose understanding of the organic regulations and natural poultry behavior lead to free-range or pasture-based production.

Organic System Plan and Recordkeeping Requirements for Poultry Operations

Every certified organic operation needs to develop an Organic Production and Handling System Plan (OSP) that describes the operation. In general, an OSP needs to include a description of methods, materials, monitoring, and recordkeeping to demonstrate how the plan is being followed. For poultry operations, this includes the following:

• Source of birds (purchase receipts or brooding/hatching records)

• Feed (100% certified organic rations, fee sources, receipts and labels for certified organic feed, approved supplements and additives, and production or purchase of organic pasture, forage or other feed crops)

• Housing and living conditions

• Preventative health care practices

• Handling practices and materials (meat bird slaughter, packaging and sales; or egg collection, washing, candling, grading and packaging)

• Production and sales records

• Labeling to be used

• Recordkeeping (documentation of all of the above to show implementation of the producer’s OSP and compliance with the USDA organic regulations)

Egg Handling and Meat Processing

In order to sell eggs or poultry meat as organic, products must be processed (handled) in certified organic facilities. Washing organic eggs or processing poultry meats may take place on- or off-farm as long as practices and materials are described in your OSP. Materials used in egg handling may include cleaners, sanitizers, and egg-coatings. Materials frequently used for poultry meat processing may include cleaners and sanitizers used on scalders, evisceration tables, chill tanks, scales, or any other organic food-contact surfaces. Egg handling and meat processing methods materials must comply not only with organic regulations, but also other federal regulations, including but not limited to the USDA’s and Food Safety and Inspection Service, Egg Products Inspection Act, Egg Safety Rule, and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s Food Code. Industry standards may also apply.

Selecting Your Poultry

USDA organic regulations require livestock producers to choose species and breeds that are well-adapted to the site and climate where they will be raised, and resistant to common diseases and parasites in that environment. Hatcheries provide breed descriptions and productivity data. The experience of other local producers can provide valuable input to guide your selection. Your buyers’ values, priorities, and preferences are practical considerations in designing your production system, and selecting breeds that thrive in that environment. Go to attra.ncat.org for a link to ATTRA publications on organic and pastured poultry production. Some customers value outdoor production, and seek birds they consider to be more flavorful. However, breeds that are well-adapted to outdoor production are better foragers in pasture-based production usually grow slower than more conventional meat breeds. Some buyers prefer the more familiar large-breasted breeds. Fast-growing birds tend to have more health and mobility problems, but reach marketable size several weeks faster on less feed. Design your production systems and select breeds with desirable characteristics to balance the health and productivity of the birds in your environment, and sustain farm profitability in varied markets.

Sourcing Birds / Hatcheries

Most poultry producers source their young stock from commercial hatcheries or specialized producer networks. Some breeds and circumstances call for sourcing eggs to brood on-farm (e.g. quail, whose small chicks are delicate to ship). According to USDA regulations, organic management of poultry must begin no later than the second day of life. Although the type of hatchery is not specified in organic regulations, poultry farm advisors recommend purchasing only from breeding flocks approved by the USDA National Poultry Improvement Program (NPIP), which certifies flocks to be free of certain diseases.

Vaccination against common diseases is allowed in organic poultry production, though vaccines must not be genetically modified. Vaccination of chicks, duckings, poults, or other avian stock by the hatchery can be requested at the time of ordering. Hatchery purchase records document animal origin and some preventive health. Other vaccinations may be done later on farm, and farm records kept for organic inspection and certification. Vaccines commonly used in the United States include those against Marek’s disease, Newcastle disease (whether this vaccination is recommended or not depends on the region), and infectious bronchitis. Other preventive health care strategies are discussed further in the health care section below.

Nutrition: Feed, Supplements and Additives

Poultry need quality feed to grow well. Good nutrition includes protein, amino acids, fatty acids, energy sources, fiber, vitamins, and minerals. All agricultural ingredients in organic poultry feed must be certified organic. Any non-agricultural ingredients used must be allowed by the USDA organic regulations. For example, oyster shell may be used as a calcium supplement to strengthen bones and eggshells. All feed rations, additives, and supplements must be listed in the producer’s OSP with their complete brand name, formulation, and manufacturer, and must be approved by the organic certifier prior to use.

Organic producers need to watch out for feed additives that are not allowed in organic production. For example, “medicated” chick starter includes a coccidiostat which is prohibited for use in organic production. Some non-organic rations include arsenic as a feed stimulant and protozoan parasite control. Arsenic cannot be fed to organic livestock and is also prohibited for organic crop production, so poultry manure that contains arsenic must not be applied to organic land.

Regulations specify that organic producers must not use feed quantities or feed supplements or additives beyond what is needed for adequate nutrition and health maintenance. Feeding mammalian or poultry slaughter by-products to mammals or poultry is prohibited. Organic and non-organic producers alike must not use any feed, feed additives, and feed supplements in violation of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) prohibits the use of hormones in all poultry production operations regardless of organic status.

The requirement that organic poultry receive all-organic feed is the main distinction between certified organic and other non-conventional poultry production systems such as free-range, humane, or pastured. The cost of organic feed varies significantly depending on regional proximity to grain production and other factors. However, perhaps the biggest price difference is based on the quantities the producer purchases. Fifty-pound sacks from the feed store are considerably more expensive than one-ton totes or bulk delivery of truck-loads. Poultry producers using humane, outdoor, or pastured systems articulate how they weigh this decision point: the value of supporting organic production of feed crops vs. producing eggs or poultry meat that are economically accessible to more consumers. Feed costs range around 70% of poultry production costs; likely more in organic. Organic production costs are higher than non-organic production due, in large part, to the higher cost of organic feeds. To maintain a viable business, higher production costs must be offset by higher prices.

Organic products garner premium prices for their value as food, but also for their perceived contribution to the greater good, such as human health, social benefits, animal welfare, and environmental stewardship. Consumer trust in a label is necessary for consumers to be willing to pay a higher price for what they value. Significant controversy whirls amid discussion of the value of organic compared with other marketing claims. There are two main currents in the discussion. One has to do with the integrity of the organic label itself. To be most credible, USDA organic regulations provide a clear and universal standard, practiced by all organic producers, in alignment with consumer expectations, with consistent interpretation across accredited certifiers, and third-party verification of all producers seeking organic certification. The cross-current is the distinction between industrial type, house-based operations and producers who place a high priority on outdoor access and pasture-based systems. The pastured producer community eagerly shows–and customers recognize–the differences in quality–visual beauty, flavor, and texture of eggs and meat from birds raised on pasture. Research shows differences in nutrition, including higher levels of Omega-3 fatty acids in products when the animals’ diets include fresh, green forage.

Preventative Health Care

Organic regulations require preventative health care of birds. Selection of appropriate species/breeds and vaccination programs are discussed above. Poultry, like all livestock, benefit from a healthy environment to prevent diseases and minimize stress. Clean drinking water is required by organic regulations, and a mainstay of preventive health. Watering systems that keep water clean reduce diseases such as coccidiosis, a disease caused by a protozoan parasite. Because poultry eat in proportion to their drinking, poultry health, growth, and productivity depend on a reliable supply of fresh, clean water. In addition to vaccines, discussed above, probiotics, or beneficial microbes may be used to establish beneficial microflora. Good microorganisms work in the poultry’s gut, by competitive exclusion, to reduce disease-causing organisms like Salmonella and E. coli.

Physical alterations of organic livestock are not allowed unless they are necessary for the animals’ welfare. Most organic producers find alterations (such as beak trimming) to be unnecessary when their systems design and husbandry provide enough space, prevent crowding and competition, possibly include roosters to maintain social order, and use other strategies to provide a low-stress environment. The Organic Livestock and Poultry Program (OLPP) would add definitions to the regulations, and prohibit some alterations (See Sidebar on page 11 for more information about OLPP).

Living Conditions

Although the land on which organic animals are raised must be certified organic, regulations do not require producers to provide pasture as a feed source for organic poultry. (Pasture is required for organic ruminants since they are natural grazers, and the regulations specify minimum time and dry matter consumption.) However, production of poultry on pasture or forage generally provides outdoor access and healthy living conditions–both of which are required by USDA organic regulations. To be certified organic, pasture-based systems must also use all organic feed, preventive health care, and avoid prohibited materials.

The quality and quantity of outdoor access is one of the main areas of debate that needs more consistent interpretation and verification by certifiers. Organic poultry must have access to the outdoors, exercise areas, shade, and direct sunlight, as appropriate to stage of life, climate, and environment.

Organic requirements prescribe a healthy, low-stress environment that is key to production. Good air quality is extremely important to birds’ health. Dust and high levels of ammonia can cause respiratory problems, Appropriate, clean, dry bedding, and regular cleaning of poultry housing contribute to healthy living conditions. Young birds–chicks, ducklings, poults, and other young birds need to be kept warm and safe from predators.

Poultry must be able to express their natural maintenance and comfort behaviors, such as roosting, scratching, and dustbathing. The OLPP and animal welfare programs specify minimum requirements for roost space, housing, and outdoor access and exercise areas, as well as limits on the size and density of flocks. Current organic regulations require outdoor access once birds have adequate feathering. The OLPP specifies quantitative timeframe requirements. Any confinement of poultry after this early stage of development must be documented and justified for inclement weather; stage of life; animal health, safety, or well-being; risk to soil or water quality; healthcare—illness or injury; sorting or shipping and sale; breeding; and for youth projects.

Supplemental lighting is commonly used in layer operations to diminish seasonal dips in rate of lay during winter months. Currently, producers describe proposed practices with respect to lighting in their Organic System Plan (OSP) which is subject to approval by the certifier. If/when the OLPP is implemented, it would provide specific 16-hour guidelines.

House-based systems can qualify for organic certification provided there is adequate access to the outdoors, direct sunlight, fresh air, and all other regulatory living condition requirements are fulfilled. The OLPP clarifies the requirement for soil and vegetation. With time and shared experience, producer capacity, consumer awareness, and policy clarification, each of these systems may become further developed, clearly defined, and transparently represented for the benefit of poultry producers, consumers, poultry themselves, and the environments in which they are raised.

Predator management is necessary for the survival, health, safety and well-being of both poultry and predators. In the interest of all creatures involved, predator management practices should prevent wildlife contact with livestock. Producers may “train” each type of potential predator NOT to perceive their poultry as food or prey. Wildlife is specifically listed in USDA organic regulations as one of the natural resources that organic operations must maintain or improve, so approaches should be non-lethal. Predator management strategies include a combination of physical barriers, (housing, fencing, daytime cover and night shelter); deterrents (“predator eyes” lights, motion sensor sprinklers), and management (regular presence of humans, and well-trained guard animals).

Organic poultry are required to have appropriate, clean, dry bedding, whether in housing or nest boxes. If the bedding material used is an agricultural crop that may be consumed, it must be certified organic. When forest products such as wood shavings are used, they need not be certified organic, but must consist only of plant products that are not treated with any prohibited materials.

Manure management is an important part of managing an organic livestock operation. Regulations state, “The producer of an organic livestock operation must manage manure in a manner that does not contribute to contamination of crops, soil, or water by plant nutrients, heavy metals, or pathogenic organisms and optimizes recycling of nutrients and must manage pastures and other outdoor access areas in a manner that does not put soil or water quality at risk.” While hydrated lime is allowed as an external pest control, it is not permitted for cauterizing or to deodorize animal wastes.

Each type of poultry production system can and should become more transparently represented for the benefit of poultry producers, consumers, poultry themselves, and the environments in which they are raised. This process takes time, persistence, producer capacity, consumer awareness, political will, and clear legal definitions for marketing terms. NCAT is working, together with our project partners and many farmers from whom we continue to gain key insights, to develop reliable information and make it accessible.

The National Center for Appropriate Technology (NCAT) is a private nonprofit organization founded in 1976. Its programs deal with sustainable and renewable energy, energy conservation, resource-efficient housing, sustainable community development, and sustainable agriculture. ATTRA is a program developed and managed by NCAT. The majority of funding for ATTRA is through a cooperative agreement with the USDA Rural Business-Cooperative Service. We are committed to providing high value, practical science-based information and technical assistance to farmers, ranchers, Extension agents, educators, and others involved in organic and sustainable agriculture in the United States.

For more information on organic poultry practices and other sustainable agriculture resources visit attra.ncat.org.